As soon as we’d pulled off the A-8 and onto the N-632, my brain kicked into gear: I’d been here before. This very same roundabout, where we’d dodged cars as we lost the trail of yellow arrows at daybreak on the second day of the Camino del Santiago del Norte.

“Sí, Sí,” I shrieked. “I know this roundabout! Then we had to cross the highway and a beagle followed us to the little beach -”

“Cat, I’m driving. Shut your pico and tell me where I have to turn,” the Novio said, straight faced and without taking his eyes off of the road, whose grade nosed dangerously down the steep N-634 that runs parallel to the northern coast of Spain.

There are two ways to see the very best of Asturias: by foot and by car. The little mountain villages and pristine beaches are out often of the reach of the rickety old FEVE trains and buses, so retracing my steps on the Camino de Santiago del Norte was an absolute treat.

Deciding to spend a long weekend in Asturias was easy – not only is it our favorite part of Spain, but the Novio and I were celebrating our birthdays, our first wedding anniversary and my pregnancy reaching 20 healthy weeks (the gender reveal was a birthday gift to us both!). What wasn’t easy were the logistics: being a long weekend in August, trains were booked or prohibitively expensive, and both of our cars were standing guard outside of our house in Seville.

We’d need a rental car if we expected to do anything.

I will fully confess that I’d never actually booked a car myself! Always in charge of itineraries and lodging, I’d traversed India, planned a trip to Marrakesh and spent six years in Spain without needing to get behind the wheel. I didn’t even know what rental car companies operated in Madrid, let alone in which areas of the city, so I used EasyTerra to score a cheap compact from nearby Nuevos Ministerios. The service compared the nearby agencies, like Sixt or Enterprise, leaving only the lodging and itinerary (also my job on this trip).

My last trip to Asturias, I’d walked from Avilés to Figueras and across the Río Eo into Galicia, the Bay of Biscay always accompanying me to the left. Three years to the day after we’d arrived in Santiago, we picked up an Opel Meriva and began the trip north.

AP-6 to AP-66 to Oviedo

Glancing at the rearview mirror just past 2:30pm, I saw a snake of cars converting the AP-6 highway into a summer traffic jam. After rejoicing in the lack of people in Madrid for the first half of the month, it seems we’d found them all.

As soon as we’d past the M-50 ring road and the traffic eased up, we stopped for a bocadillo at a roadside bar. All epic road trips in Spain feature a simple sandwich on a dusty road, after all. The Guadarrama mountains melted into the arid plains of Castilla – where I’d studied abroad – before we caught the AP-66 at Benavente.

An hour later, we’d exhausted all radio stations but Radio María, but the music went off, the windows went down and the Picos de Europa rose before us, signaling our passage into Asturias.

A-8 to Faedo

As soon as we’d diverted past the capital of Oviedo and gotten on the A-8, I was flooded with memories of blisters, long walks and conch shells. I began remembering small details of our 200-mile hike, from memorable meals to cat naps in the shade of a picnic table.

We turned off the highway at exit 431, and my eyes grew wide.

“I’ve been here! I know right where we are!” Guiding the Novio around the roundabout by way of the spraypainted arrows, I was almost delighted to find that the next roundabout was under construction, just as it had been three years earlier. I could feel my calves tighten as the narrow road climbed downwards, past road signs announcing the Camino’s crossing over the highway and remembered our descent towards La Concha de Artedo.

At the bottom of the hill, we entered onto a mountain road that climbed out of a thick forest to hug curves around rolling, green hills dotted with hamlets and dairy cows.

Soon after, my mobile signal was lost. It wouldn’t be back for most of the weekend.

Faedo to Oviñana

La Casona del Faedo said it was in Cudillero, the technicolor fishing village I’d visited on my first afternoon of the Camino. It was an inexpensive, so we booked without realizing that it was in Faedo, a miniscule farming village in the Consejo, or district of Cudillero. But the air was crisp and the farmhouse was quiet, save the far off tinkling of cow bells.

Ángel showed us to our room in the 130-year-old stone stucture, having recently reopened the family home after more than a decade in Lanzarote. He hailed from Pola do Siero, just like my mother-in-law. The internet signal didn’t reach our room – and neither did the 4G – so we passed time asking him for recommendations for food and sites.

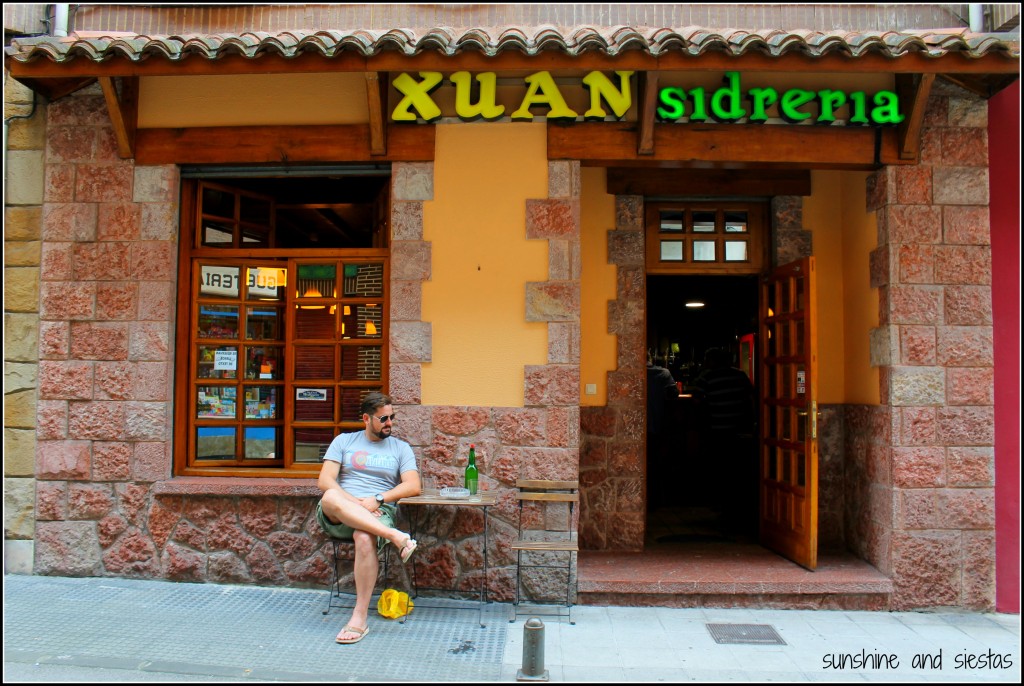

Dusk fell over the valley, and we were back to the winding CU-4 towards the A-8. In Oviñana, we drove narrow roads to Sidrería el Reguerín. There was no place to sit on the patio, so we sidled up to the bar and had a bottle of cider uncorked before I could even ask for a free chair. The culín de sirdina was tart and cut straight through the acidity of the octopus salad set before us.

This is one of those places that has a set menu, but it’s always better to order whatever is written on the chalkboard.

Downing another swig of cider and perking his nostrils, the Novio dove right into Asturian cuisine, ordering an immense cheese platter with quince pastes that disappeared within minutes. I’d have been satisfied, but no sooner had I run my finger along the knife to eat the last few crumbles of cabrales, a dish of fried zucchini stuffed with crab meat came out. The murmur of dinners grew louder as cider glasses were slammed on the wooden bar in rapid-fire fashion.

I took the wheel this time, nervously driving back towards Faedo on the hilly, unlit road.

Faedo to Muros de Nalón

Agustina wiped her hands on her apron as she walked out of the kitchen. “Can I interest you in some of my freshly baked cakes?” We gladly obliged as Ángel poured the Novio a coffee from an aging copper pot and followed it with fresh milk from across the valley. Agustina had been up early making a cinnamon coffee cake and pestiños – a honey soaked, fried pastry.

The Novio inquired about where to get the best smoked sausages and fava beans as Ángel nervously checked his watch. “You should hurry and get to Muros de Nalón. They’ve got a weekly market on Saturdays with just about everything.

A quick gulp of coffee later, and we’d jumped into the rental car and zoomed down the mountain, windows open all the way and the Novio’s hair, normally weighed down with hair gel, gently flapped in the wind.

Muros had been one of the first towns I passed through on the Camino, upon leaving Avilés and walking in a few circles around Piedras Blancas. We’d rewarded ourselves with a beer before the last ascent into El Pito, where we’d splurged on a nice pensión. The car came to a halt just under one of the blue and yellow tiles marking the path into the center of town and the market.

More than food stalls, we found clothing stands, used books and more people milling about the bars than the small market. While the Novio checked out the long coils of chorizo and morcilla, my nose drew me to the baked goods, where I bought a loaf of bollo preñao: sweet chorizo, strips of fatty pork shoulder and a few boiled eggs baked into warm bread.

Lunch was solved for 5,50€.

The Novio’s stock included six or eight links of both morcilla and chorizo to make fabada, a hearty bean stew. He downed a few culines of cider before we pointed the car down the hill towards Cudillero.

Muros to Cudillero

Our first night on the Camino included a stop in Cudillero, dubbed as one of Spain’s most beautiful villages. Tucked into a natural bay and protected by rock formations, the sleepy town bubbles over during the high season. And interestingly enough, the town is said to have been founded by Vikings who sought a safe port in its natural breakaways, leading to a local dialect, Pixueto.

In late July, 2013, our legs had been too tired after 26 kilometers to do much else but have a taxi pick us up in El Pito and take us right to the port and its cool, pebble-streaked waters and central cider bars. Three years later, the Novio and I climbed the stairs leading away from the village center to the carefully stacked houses and sidewalks that tumble from the cliffs.

Cudillero was just as quaint and colorful as I’d remembered it, though so overrun with tourists that I felt overwhelmed and uncomfortable. Just a simple look over his sunglasses was all the Novio needed to say for us to retreat to somewhere a bit quieter.

Cudillero to Soto de Luiña

“Which way to the Pilgrim’s Inn?” asked the peregrino, eyes, squinting in the hot afternoon sun. His face was streaked with sweat and a bit of dirt, evoking memories of ending up, at 1pm, in much the same state. I pointed up the road, indicating that he make a right just after passing the church, where he’d find a bed for cheap in an old converted hospital.

The Novio put out his cigarette into a conch shell ashtray as we watched a few more scattered pilgrims arrive to the bar we were sitting in front of, dip in for a cold drink and continue on to a nap. The bar was the first in Soto de Luiña – and based on the fact that it had run out of food by 2pm, it was likely the most popular.

We’d walked steadily along the A-632 that morning, dodging cars and cyclists on our way to Ballota and its virgin beaches. The Novio bought a bottle of beer and a bag of chips and instructed me to wiggle into my bathing suit while we drove towards the nearest beach.

Soto de Luiña to Playa del Silencio

I’d often heard that Playa del Silencio was one of Asturias’s best, given that it was inaccessible if you didn’t arrive on your own two feet or in a sailboat. Cradled by a sheet rock cliff and a thick forest, the nearest “village” is several miles away, and there are no chiringuitos or even a lifeguard stand.

The car park led us to believe that the place was crawling with beach goers, but most we met on the way were heading back from the beach. The gravel path led down to nearly 350 stone steps that were narrow enough that onlyone person cold pass comfortably through.

My nice leather sandals crunched uneasily over the smooth stones that made up the beach. Even with the 513 meter stretch of beach full of people, there was… silence. Save the breeze whipping past mey ears and the ocean lapping at the rocks, it was eerily silent.

We passed the bollo preñao between us, contemplating the next 20 weeks and what would come after. I treated our weekend as a babymoon of sorts, a few fleeting days when it would just be the two of us, when we could called the baby “Micro” and when my belly just looked like a little bit of bloat. I plucked my straw hat from my bag and rested it gently over my face, succumbing to yet another afternoon snooze – savoring every one of them I’d get before the baby arrives.

Playa del Silencio to Luarca to Puerto de Vega

Washing the salt off of my body, I heard the Novio downstairs speaking with Ángel as his beer glass clinked against the wooden picnic table that we’d come to claim as our own. Not only was it a long weekend, but it was when many villages in Asturias celebrated their local festivals, making for a madhouse in villages that didn’t have the infrastructure for so many cars, tourists and hungry bellies.

We decided to try for Luarca anyway, another large fishing town where Hayley and I had spent a night. I remember finding it devoid of much life – it was grey (the water in the bay included) with most of the town shuttered up, despite being called the Pueblo Blanco de la Costa Verde. But in fiestas, it might just prove to be a bit more lively, and local favorite El Barómetro told us they had space at the bar for two.

We drove in circles around the large port and up to the picturesque cemetery looking for parking, but it was futile – we were onto the next village, Puerto de Vega, as soon as we’d determined that even the vados had been taken. Puerto de Vega was decidedly sleepier, but for Casa Paco. We nabbed the last unreserved table in the dining room, a chill chasing us in from the port, where a few white and red fishing boats bobbed up and down with the wake. The octopus was tender, the cachopo – a pork loin wrapped in cheese and ham before being deep fried – as long as my forearm.

That night in Faedo, I didn’t last five minutes in bed (with covers on!) before I fell asleep to the lull of the diners in the bar below, waking up the following morning to crickets and cowbells as the fresh dew still lingered on blades of grass.

Faedo to Grado

We skipped the pestiños in favor of fresh cheese bought from the neighbor and crushed tomato on bread that Augustina pulled out of the oven with heavy mitts. Unsatisfied with yesterday’s yield of products, the Novio had already spoken to her about the market in Grado. Due to its position in a flat, fertile valley, the consejo is rich in gastronomic tradition, particularly cheeses under the D.O. L’Pitu and beans.

The roads were foggy and damp that morning as the car slid down the valley into Villafria. Ángel gave us instructions as only a born and bred asturiano could do, full of local words I couldn’t grasp, waving hands and landmarks.

We somehow arrived without getting lost (though we had to screenshot the way on our phones due to lack of a mobile signal).

Known locally as Grau, the entire town shuts its central streets for the massive weekly market, and shops stay open, closing instead on odd days. We fought our way through crowds and vendors hocking socks, fake watches and clothing to the Plaza General Ponte, where the traditional market has run every Sunday since 1258. I went to check the free samples on cheeses while the Novio proudly announced that the chori-morci he’d bought the day before were fresher.

We tagged team the whastapps, making the rounds to ask which family wanted fabes or fabines for winter stews. A kilo of good quality fava beans in Madrid was nearly twice as expensive at 20€/kilo: prices in Seville could be up to 10€ more! We walked back to the car with arms laden with cheeses, pig shoulder and beans, stopping briefly at a sidrería for a refreshment.

Our late start meant we’d finished shopping right about lunch time. Agustina had suggested the hearty menu at Casa Pepe el Bueno which, at 17€ per person per menú del día (on a weekend!), was more than we’d paid for a meal all weekend. The low-ceilinged restaurant was as stuffy as it was packed with people. For a starter, we both chose fabada, served in an enormous silver bowl, meaning two plates each.

“Now Micro knows what a true fabada is,” the Novio mused, pushing back his chair as his cider-drenched hake was set down before him.

I was able to make room for dessert as I felt the first small rumblings of our child – a quarter Asturian anyway – deep in my belly. That, or a satisfied stomach.

Grado to Playa de Concha de Artedo

The road back from Grado was far bumpier – I nearly scratched the car on the narrow road behind Pepe el Bueno, stalled twice due to the car’s sensitive gears and was kindly asked to just navigate us back to Faedo. We made it as far as Pravia before losing signal and relying on our instincts to guide us.

An hour later and after risking bottoming out on an old cattle route, I collapsed into bed as clouds rolled over the valley, heavy with rain.

Slipping on my bathing suit – still a bit damp from my dip the day before – we made one last beach stop at La Concha de Artedo. I’d been but a kilometer from this beach on our second morning of the Camino, and smiled remembering a beagle that followed us from the restaurant at the top of the hill all the way down to the next arrow.

It was chilly but the time I’d found a dry rock to rest my bag, but the Novio was already darting between rocks, looking for baby andarica crabs that had been washed in with the tide. The pools were warm and shallow, hiding the creatures under rocks full of bígaros and clams.

Due to a goof up in our room, Ángel and Agustina had offered to invite us to dinner at the casona, free of charge. Being one of two restaurants in Faedo – the other was a vegan music bar, quite modern for a town whose population hadn’t topped 150 in half a century – she cooked nightly for more than just guests. As dusk fell, the Novio and the propietario shared a few culines of cider and we chowed down creamy croquetas stuffed with local chunks of chorizo and pito al chilindrón, a simple chicken dish in which a whole chicken is cooked and stewed in a vegetable paste.

“Mi mujer tiene mucha mano en la cocina,” Ángel would later claim as we thanked them for the phenomenal meal. Indeed, Agustina was a kitchen whiz.

That night, the wind ripped opened our heavy wooden shutters. Lightning pounded the valley, and as I lazily pulled the windows shut and locked them, I couldn’t help but think that there’s no wonder the animal products up here taste better – it rains so much!

Faedo to Lastres

“Bueno, hoy es tu día,” the Novio stated, taking a long drag off of his cigarette as Ángel set a glass of fresh juice in front of me. “What’s on the itinerary? It was my 31st birthday, and I wanted to do what any other 31-year-old-woman would want to do: Go to a dinosaur museum.

I patted Chispa on the head once more and thanked Ángel and Agustina for their hospitality. Checking the route before we’d be left without internet once more, we rolled down the Meriva’s windows and slipped back down the mountain.

Passing through Colunga before reaching the Museo del Jurásico de Asturias, we gobbled down the rest of our bollo preñao in the parking lot. Being a national holiday, the museum was teeming with kids. I nudged the Novio in the ribs, knowing full well that we’d be skipping the bars for kid-friendly activities in a few short years.

The northern coast of Asturias was once home to a number of sauropods during the Jurassic period, and the Las Griegas beach has uncovered a number of bones and the largest dinosaur footprint to date. Forming part of the Costa de los Dinosaurios, the museum is one of Asturias’s top tourist attractions.

For someone whose favorite college course was based on the prehistoric beasts, I was a bit skeptical due to the number of reproductions (I am a purist, oops), but to have free election over what to do that day, I enjoyed pointing out the different features of dinosaurs and goofing off in the reproductions park.

Lastres was just around the bend of the AS-257, another quaint village perched on a cliffside. The stone houses reminded me more of the southern coast of France than the northern coast of Spain, with its red roofs and bougainvillea spilling out of window pots.

Though we’d eaten everything on our list – from cheese to fabada to bollo preñao – the Novo hadn’t had vígaros. As a kid vacationing near Lastres, he’d pick the shiny black mollusks off of rocks and dig out the worm with his fingers rather than using a straight pin.

A waitress spread an old, faded tablecloth at one of the beachside restaurants once we’d descended the stone stairs to the small port. As a summer baby, I was clear about lunch – freshly caught seafood. Time stopped for an hour despite the ancient clock tower ringing every quarter hour. As the restaurant where we sat on stools fishing the vígaros out of their shells filled as the lunchtime hour creeped slowly up, we ordered a plate of razor clams, piping hot with a hint of parsley and lemon, and squid in black rice.

I’d have a birthday pastry at some obscure rest stop a few hours later, the Novio promised.

Lastres to Madrid

Tempting fate, we decided to return to Madrid a bit earlier than planned, checking the traffic report on RNE every hour. Once again, we had the Picos behind us in the rearview mirror after an hour, then the Castillian plains before ascending Guadarrama and entering back into the capital.

Perhaps on my next trip to Asturias – Micro in tow – we’ll focus on the oriental part of the region. The Lagos de Covadonga, the tiny mountain villages tucked into crags and providing sweeping views of Bay of Biscay, the artsy cities of Llanes and Ribadasella. Or perhaps he’ll eat cheese at el Reguerín and hunt for crabs with his father at Concha de Artedo.

It’s easy enough to explore Asturias by bus or train, I suppose, but half the fun are the tight turns, the stoping for cows and the sleepy little hamlets where vecinos wave you down to try and sell you their fresh milk or butter. Save walking along the coast, it’s the only way to go.

EasyTerra Car Rental, a Netherlands-based rental agency that compares well-known suppliers in more than 7,000 loctions worldwide, graciously picked up our tab. We paid for gas and navigated tractors trails and tight mountain curves ourselves – so all of the opinions expressed here are my own. That said, their website is user-friendly and their prices are the cheapest we found!

Have you ever driven or walked through Asturias? What places would you recommend?