My ride is a bubblegum pink cruising bike with rusted handlebars, a rickety frame and the name Jorge. Since I live outside the city center (ugh, I know, don’t remind me), I’m constantly busing myself from one end of town to the other to meet friends, run errands and go to work.

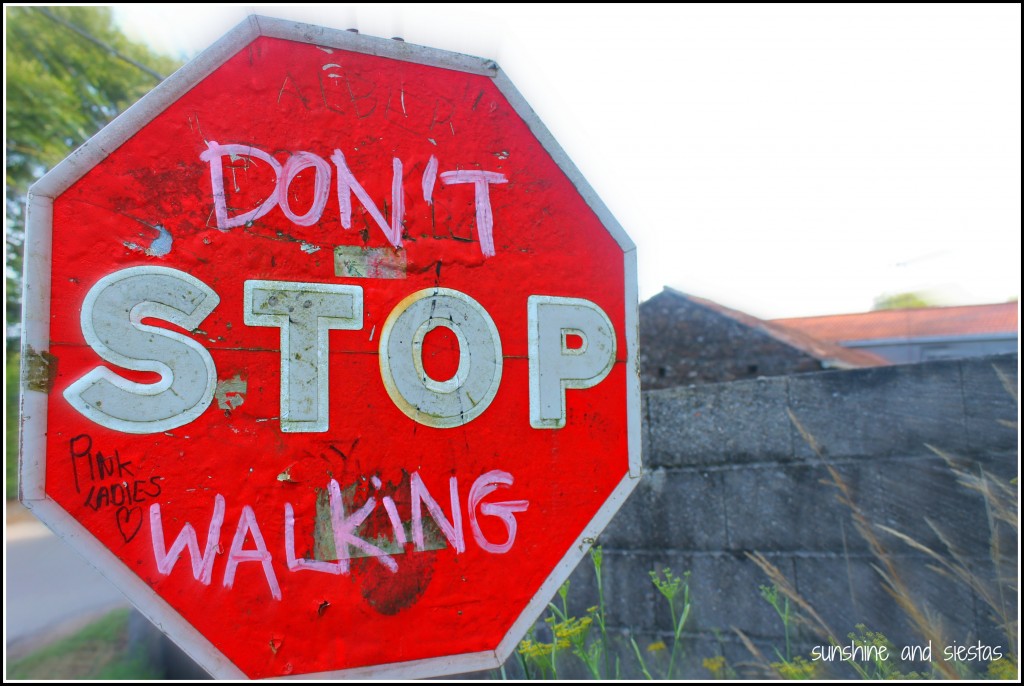

When I was a kid, I couldn’t wait to come home from school and ride my bike around the block until my legs practically fell off. Now that I’m an adult, it’s my favorite way to get around, especially in a city with terrible transportation and few parking spots.

Seville is perfect for bikes – it’s flat, has miles of bike lanes and so, surprisingly, nearly one-tenth of sevillanos chose to commute on two wheels. For me, there’s nothing more freeing than pedaling along the Guadalquivir, feeling the burn in my thighs and arriving a little winded to work or to meet my guiritas.

Consider renting a Sevici bike, part of the city’s bikeshare program, for half of what a cab costs from the airport. Yes, the bikes are big and clunky, but it’s the easiest way to get from one place to another. For one week, you can use the bikes for 30 minutes (o sea, between bars or between practically any point in the city), and there are more than 250 rental points.

Is your city bike friendly? Does your bike have a sweet name like mine? For more videos, subscribe to my YouTube channel!