A round lump rests each year at the bottom of my stocking. This gift, a California orange, is something we get every year from my grandfather, who signed us up to get a huge crate every December, even though he’s been gone for years.

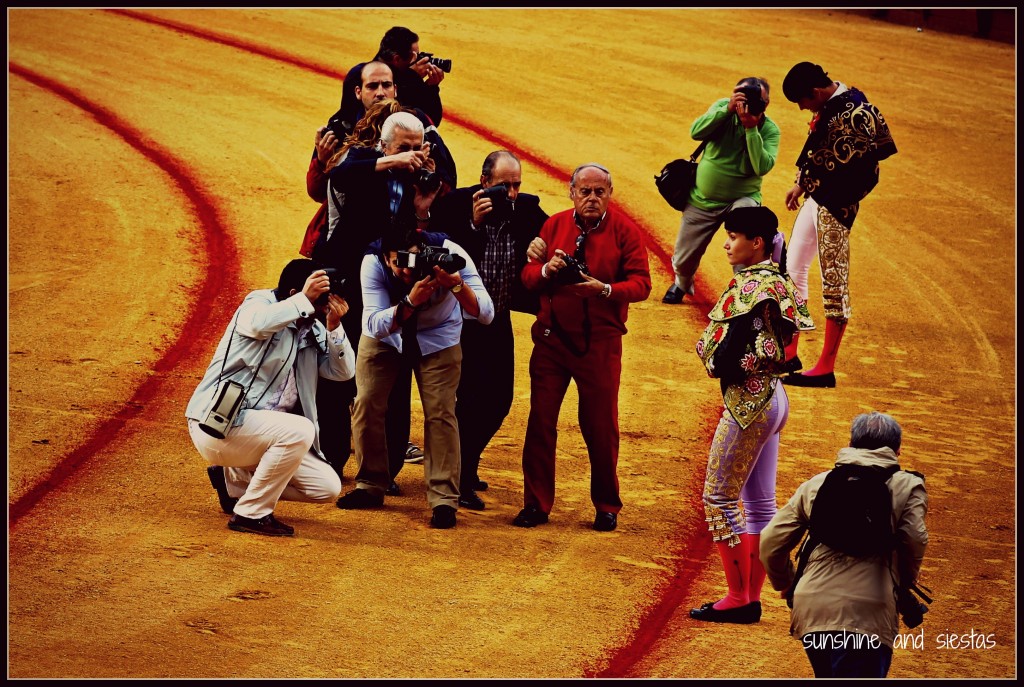

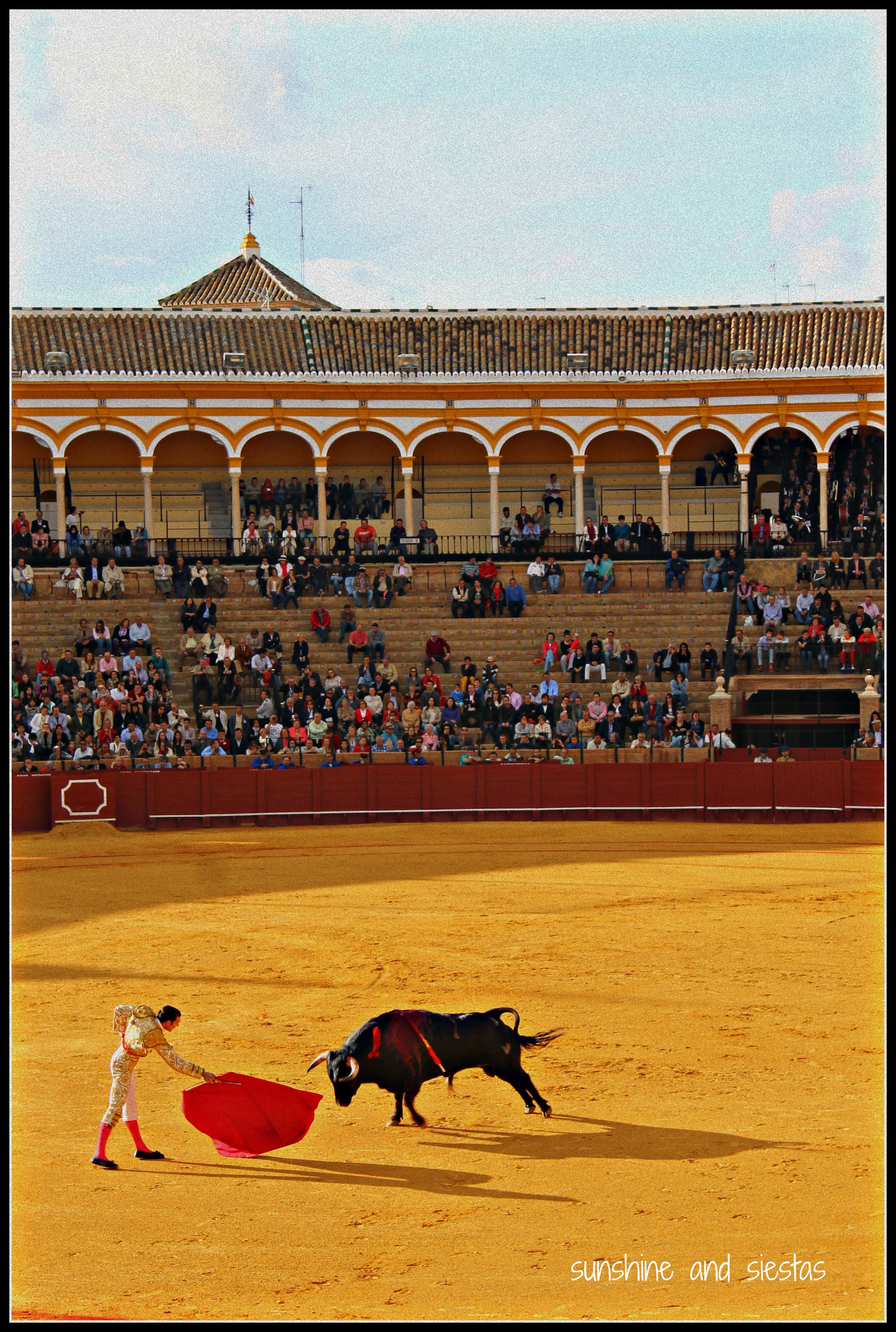

It’s hard not to think of him when I see the beauties growing on the trees just outside my door. A dull smack, and one hits the ground rolling. While they’re not to be eaten in Seville (they’re used to make bitter marmalade), we often pick them up and make a cheap air freshener out of them. Just like a bullfight is characterized by three acts, culminating in the final faena, so is the life and death of the naranjas, whose final rebirth is a fragrant flower called azahar.

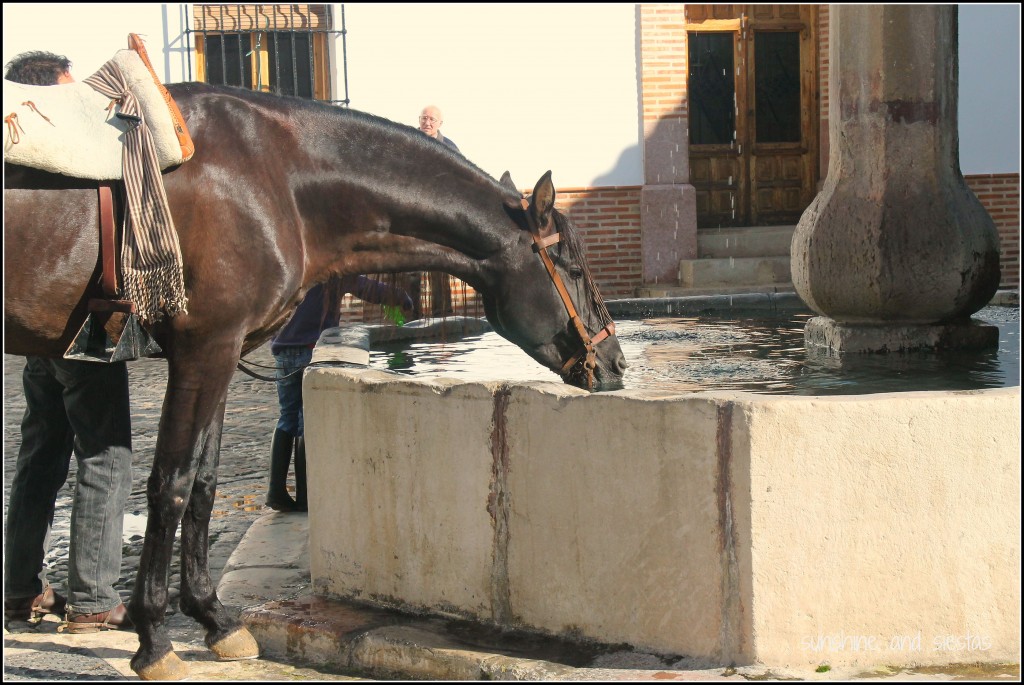

Orange trees enjoy the temperate, rainy winters in Seville. Come mid-February, the thunks become more frequent as workers use metal poles to dislodge the naranjas from their trees. The fruit is then gathered into large crates or burlap sacks and shipped off to Merry Old England.

Within days, the springtime rains bring along the small, silky buds that pop out amongst the waxy leaves. Sometimes they open early, filling the nighttime with a clean scent. My Irish friend claims they always come up around St. Patrick’s Day, so my nose has been upturned for the last few days, waiting.

Like all things springime in Seville, the azahar petals fall to the street within a few weeks, and the tempratures shoot up into the high 20s. The azahar is overpowered by incense from the Holy Week parades, and then by fried fish and sherry during the April Fair.

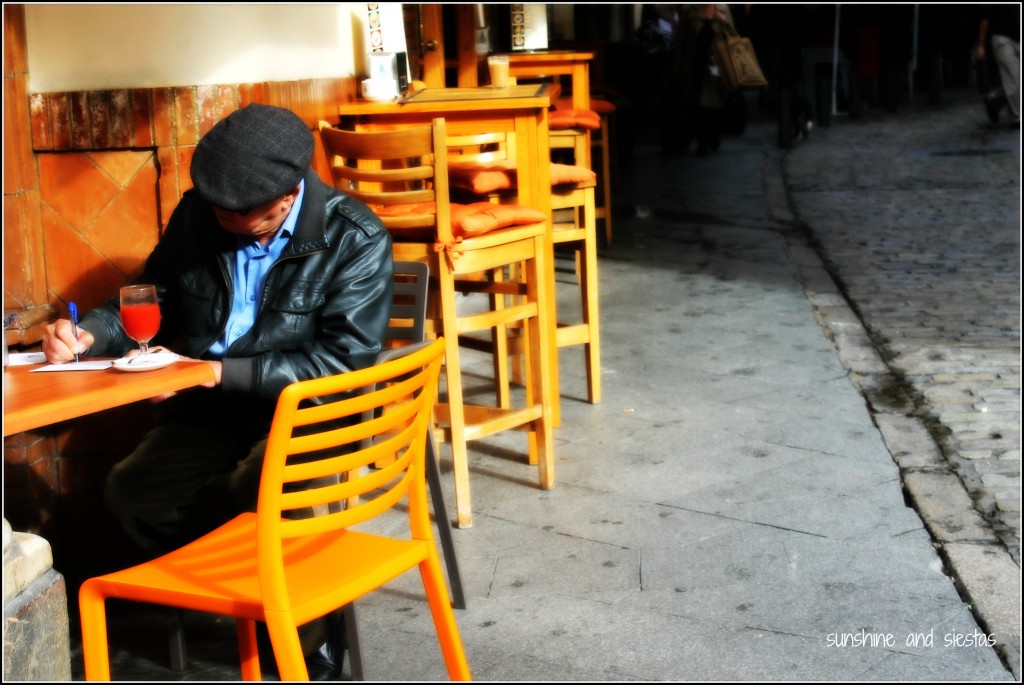

My friend told me that if I liked Seville during the Autumn and Winter, I’d swoon in the springtime.

She was right.