2020 will be the year that the world stopped for so many. But for me, it’s the year I got to live in France.

France was a lovely little séjour, despite those pesky aspects of living abroad. Every pain au chocolat reminded me of being 16 and traveling around France with my grandfather, every new word learned was a small personal victory to untrain myself from Spanish while slowly making sense of street signs and school communications. In a year where no one traveled, a summer of exploring a new home base became our salve, the balm that soothed away all the scary stuff and ever-present threat of the virus.

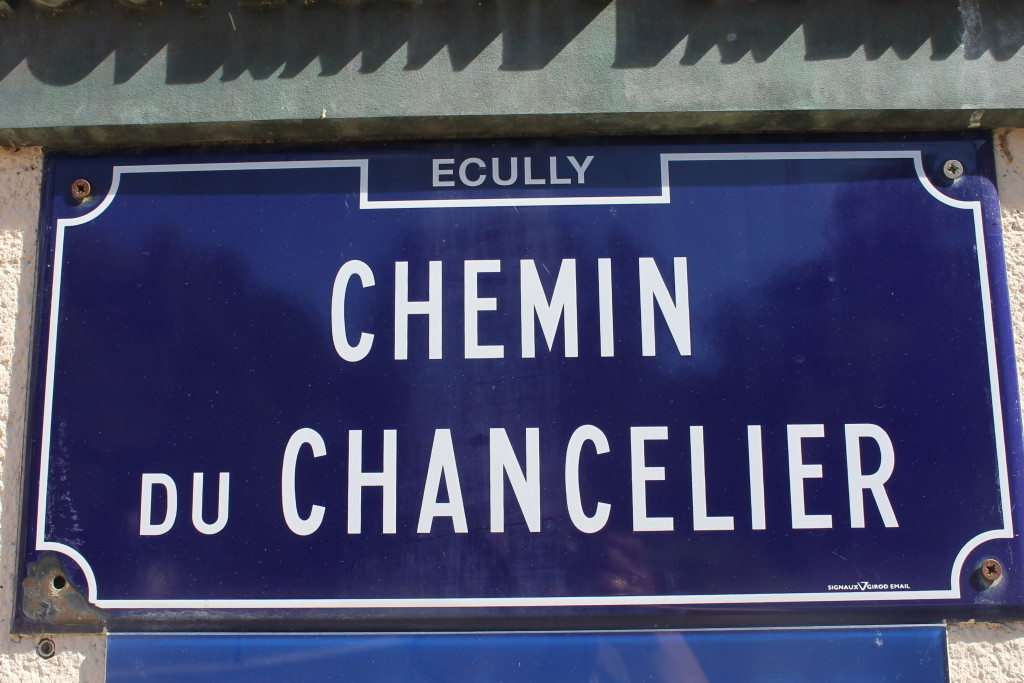

We spent six months living in Écully, a wealthy village of 18,000 people just west of Lyon. The largest park was on the grounds of an old château (now home to Lyon’s premiere cooking school and the only hospitality school restaurant in France to hold a Michelin star), the village church and Liberté-Fraternité-Egalité-emblazoned mairie anchoring a small downtown that was once the carriage route to St-Etienne. It wasn’t Belle’s Alsace but it was pretty damn cute, the homes named for flowers, doors overgrown with lilacs and ivy and random châteaus hidden behind apartment complexes.

I didn’t blog. The attempt to jot down a vignette or two every week suddenly seemed a momentous task after a day trying to fumble through French and not get lost and perfect a quiche lorraine. I truthfully didn’t want to find the time to do it. And now, half a year since we returned to Spain, I am ready to talk about it. And, truthfully, I don’t want to forget.

I have been a Francophile since I was a kid. Maybe it was growing up reading Madeline, or my mother’s obsession with French silk. I begged her to let me learn French at a fancy sleepaway camp in Minnesota, something I’d read about in a magazine. She scoffed that I could go to the park district camp and wade in a creek instead of drowning myself in baguettes.

By the time I was 13, she signed the permission form to let me start language classes – Spanish. I got the last laugh when I married a Spaniard and Nancy lost me to the mother continent.

Lyon. While Paris has long swooned me, I fell deeply in love with Lyon. The city is home to the second largest urban area in France, crowned by the Monts d’Or and framed by the confluence of the Rhône and Saône rivers. Les gones – a nickname given to the lyonnaises – are comme si-comme ça about all things Parisian, crown themselves as the gastronomic capital of France and have witnessed some of France’s most emblematic events. The Romans. The Gauls. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. The Lumière brothers. Jean Moulin. Paul Bocuse.

Mon dieu, I was in love with this place before even looking for flights, much less asking permission to work from another country. I would wind my way through the streets of the Croix-Rousse like the old canuts, dine in every restaurant Bourdain had stopped in on Parts Unknown and pick up my produce and cheeses that reeked of grass and the countryside at the Saturday morning market. I had dreamed of living in France since kids were learning French on tapes, and it was finally happening. Quelle aventure, la France!

March 2020

As the weather warmed, so did my urge to get planning. When I first moved to Spain, fresh out of college, I literally left just about everything to chance. I had spent a few days in Seville and knew I liked it, but the prospect of living there didn’t register when I was subsiding off of gazpacho in the July heat as a study abroad student.

We interviewed with a relocation company that specialized in expats one afternoon. As the Novio’s job as a civil servant got a delightful smirk, hearing I was American and hadn’t yet mentioned the prospect of moving was troublesome to her. Add in two kids who needed schooling and a budget during a housing crisis, and she declined to work with us. I was aghast: someone was refusing our euros?

Little did I know just how much I would hear the word non when we eventually got to France that summer.

Well, then the rest of March 2020 happened, and I promptly cancelled my trip to the U.S. that summer and planned on an été français.

April – May

One silver lining of the pandemic is that housing options suddenly opened up, meaning that the offerings were suddenly ours for the picking. We weighed commute against price against outdoor space (post-pandemic trauma is real) and found a suitable place in Écully. I loved its proximity to the city of Lyon and the village’s town center; my husband loved that it was 1.5 km from the autoroute and only 20 minutes to his new headquarters.

After we’d booked our house, schooling for Millán suddenly got solved, too. I had long heard the praises of the public education system in France, but that a spot at a crèche was about as difficult as getting one at an elite preschool in New York City. I took to Facebook as any old millennium would and immediately found a Facebook group called Españoles en Lyon.

Un tal Fulanito messaged me, un voisin d’Écully by way of Huesca, and he sent me the inscription forms, detailed information about timetables and the names of a few good places to check in town. On a whim, I called one, not even realizing that there was a crèche a lot closer to our new digs.

“Âlo?”

I tried, in French, to ask about inscriptions. She told me someone would call back (I think), and he did (thank goodness), but it wasn’t until he wrote me an email that I thought to ask if he spoke Spanish or English. François (“me llama Ud. Paco, s’il vous plaît!“) was half Spanish, with an andalusian surname.

As it turned out, the woman who appealed to the mayor, Mme. Parfait, had called that morning to ask how many spaces François would need, and if I could just send the baby’s birth certificate and our proof of housing, he would ask for a five-day spot for Millán.

This.could.not.be.more.perfect.

It was all falling into place. Enrique’s school was LITERALLY across the street, and Millán had somehow gotten a spot (COVID, you fickle bitch). We had a home, my Spanish to French translations had arrived, and I could finally start dreaming about ma via française.

I bought tickets for July 2, direct to Lyon from Seville.

June

As Seville began to awaken and we could finally leave our homes, that travel-panic mode kicked in. I still hadn’t learned any French and, despite having everything seemingly under control, I’d never been more wound up. The pandemic definitely made my anxiety shine hot and bright, and my family was often on the receiving end of grunts and shouts. We made tentative plans to come back in late October, when Enrique would have a school break, so I dutifully packed our bags for the summer and early fall, chose a few toys and books and helped the Novio pack the car.

He arrived to Écully on June 23, found the nearest supermarket, his way to work and a few other Spanish families. I moved in with his parents, juggling the kids and work while tip-toeing around my father-in-law’s schedule. As I was sending out an email invitation to 40,000 juniors in high school, I received an email from Transavia that my flight had been cancelled.

I rebooked on Air France for the same day, via de Gaulle, forwarding my mother-in-law the tickets to print.

Oye, niña: Millán’s name is spelled incorrectly, she announced as she passed them to me.

I was aghast. HOW could this be happening? She shooed the kids away while I called Air France. And waited. And waited. In a post-COVID world, there were so few operators that I was on hold for hours before the agent told me I’d have to call Air France in France. Cue more hours on the phone, a credit card that had reached its limit, my American card assuming the purchase was fraudulent and the tickets on July 2 selling out. I was nervous that borders would close just as soon as they’d opened up, so I hastily booked us onto the July 4th flight via Paris. It was three times as much as I’d paid on Transavia originally, and my privilege was on full display right then and there. I could afford to book and rebook – what would it be like fleeing for our lives when I was crying over an extra two days in Spain?

July

We made it to July 4th. As my mother-in-law helped me wheel the bag to the check-in counter at the Seville airport, I felt a sense of relief that we were almost there, that my gumption (or truly just my stubbornness) had got us this far. Millán slept the whole flight to Paris, waking up as we touched down. The airport terminal was practically a ghost town, but that didn’t stop my kids from rolling around on the ground, sticking their suckers on every surface and pulling their masks down.

Let me remind you that the early summer months was a very small breath of air, like breaking to the surface after being underwater. There is the awareness that the virus is still circulating freely but no one has really, fully let down their guard.

Breathe, Cat. You will be fine.

Only NO ONE in France was wearing a mask when we arrived. The enormous Carrefour in Grand Ouest didn’t enforce them until later in the month when cases began to climb. Vieux Lyon, a UNESCO World Heritage site and huge tourist draw, merely suggested wearing them indoors. My family were the only weirdos masking up unless we were eating because we didn’t want to be assholes (and we didn’t know enough French to survive a hospital setting – despite everyone needing a hospital but me during our stay).

But WE WERE IN FRANCE.

I got to exploring the village in our first days, not wanting to spoil Lyon by going without the Novio. We found all of the bakeries, slowly working from one end of the display case to the other, with me clumsily ordering coffee. The betting house had cheap beers, so we stopped there after the park for Super Bocks and a sirop, the French version of a soft drink, for the kids. I even got a loyalty card at Picard for frozen foods.

Le (merde de la CAF)

One morning, we marched over to the town hall and asked to speak to the woman in charge of school assignments. She was impressed that I had gotten my documents translated to French and – voilà, Madame – gave me the cell phone number of his Spanish-speaking teacher, who wrote me an email that same afternoon.

I called François at crèche and asked about the adaptation process for Millán and how to complete his registration. Do you have the CAF? he probed, telling me that he could not finalize the process nor tell us how much we would owe for care until he did.

And thus began the two-month odyssey into getting Millán registered for daycare. The CAF, or the caisse des allocations familiales, is the social services body that serves families and young people, often giving rebates according to salary. When creating an account online to request our family allowance, I realized I’d need a French phone number. That was easy. I’d also need a French bank account. Every bank we tried told us no – either because of U.S. tax laws, or because I’d tried to get a bank account without my husband’s signature (who could guess that the patriarchy in France was more dominant than in Spain?). One flat out refused because he said our short stay was not worth his time. The Novio was frustrated by having to take time off of work, and the CAF refused our Spanish bank number.

There was a bright spot: when we stopped by LCL, a woman heard us discussing the situation in Spanish. Odiel, a widow who had lived in Écully her whole life, offered to accompany us to other banks as a translator and quickly became a friend.

By the end of July, we had finally succeeded in opening a compte nickel, which is an account that is typically reserved for refugees before they are fully established. We kept the minimum amount – 20€ – in the account and paid Enrique’s school cantine through school intranet.

Bank account and French number in hand, I applied for the CAF number online and went to Social Services to request help. After 10 minutes of bank and forth and calling another social services office, I was told to stop the following morning for a doctor’s appointment and to speak to the official in charge of the CAF in town. We were getting somewhere! I treated myself and the kids to macarons as the church bells rang. Because it was noon. And, just like Spain, everything closed in the middle of the afternoon.

The following morning, I showed up at the Maison de la Metropole, a trailer in the middle of a dirt lot. We saw a doctor, who spoke enough English to give my kids a clean bill of health and a few hints about the CAF, and then said they’d be closed for the entire month of August. Damn, Europe.

August

When I wasn’t dealing with bureaucrazy, Millán turned a year old and began walking, we spent a lot of time on our terrace and in the yard with the neighbors and finally exploring the city’s museums, parks and bakeries.

It could have been easy to mourn the loss of our summer in the U.S., but every weekend brought the opportunity to see how much we could cram into 48 hours. The hilltop Dauphinais castle at Allymés, followed by a walk around Pérouges. Down to Grenoble and to Vienne. We even made it to Geneva on our wedding anniversary and to the Black Forest to celebrate our birthdays. The weekdays meant working while Millán napped and spending the afternoons somewhere – often a park, a château or a park next to a château.

Enrique woke up most mornings asking, “Where are we going today, Mommy?” My intrepid three-year-old definitely takes after his mother.

I would occasionally meet other families at the park who spoke English, or who I could cobble together our basic story. But my very Spanish children couldn’t muster getting out of the house before noon, which meant that the parks were often for us while families had their midday meal.

September

In late August, I took Millán to the adaptation days for the crèche. It was lovely to meet François, who was gracious but told me it was impossible to do anything without the CAF because the computer system wouldn’t let him input information.

In the meantime, I looked for childcare options for Millán. Getting an assmat, or an assitante maternelle, was also impossible without the CAF, and the micro crèche in town was 800€ for five days, part-time (we pay 280€ for full-time in Seville). I took to Facebook again, where we found a lovely nanny who had lived in Chicago before coming to Europe, and she watched the kids each Wednesday and on school holidays. Oh, yes – Enrique had no school on Wednesdays, so I decided to keep Millán home, too. My kids adored Natalia, and as Millán napped, we got to know one another over tea.

Taking Enrique to his new classroom on September 1 was a slow, steady build up to a taste of freedom. For nearly six months, they’d been my little shadows. It was hard to work, to exercise, to sleep with the constant interruptions of kids. But it was also bittersweet after six months of new adventures, new milestones and time to grow as a family unit.

François called shortly after the start of the term and told me that we’d been given a provisional CAF number but had to present a number of documents. So, it was back to Maison de la Metropole, but I asked the Novio to come with one of his French coworkers for assistance. They took our documents, bank statements, copies of our family book and maybe two years off our lives due to stress, but we were finally given a provisional CAF number that was set to expire on December 31.

The next step was to petition for the spot to the mayor, who would have to cover any extra expenses if we weren’t able to pay for the schooling. At the end of September, I had both boys in school four days a week. Formidable, non?

October

Some time in mid-October, I suddenly felt adapted. I didn’t rely on my GPS or I didn’t fumble over my words at daycare to tell them when Millán had woken up (only to discover, a month later, that I had reversed word order). The library and children’s center recognized my children as les americains. I learned that the 69 on the license plates corresponded to the metropolitan district. Auverge-Rhône-Alpes shrunk to the Rhône shrunk to the le Metropole to le Grand Ouest and to Écully. Our world seemed small yet expansive simply because it was different.

We’d been to the big draws, and I jotted down small museums and villages to visit in our second half. There were wine harvests and film fests, and we’d hardly ventured to what Lyon offered further away from the Presqu’île.

“They’ll never shut our museums or cinemas, pas les choses culturelles,” they whispered. Enrique was home on a Tuesday, thanks to the ever-present vacances in the French school system. We said goodbye to his sitter and I stuffed him quickly into the car, got some McDo and found a spot to park in Vieux Lyon. Another lockdown was imminent so I wanted to take him to see one more Guignol. A distant relative of Punch & Judy, Monsieur Guignol is the beloved lyonnais puppet whose shows were social commentary on the buttoned-up Catholic society in the early 20th Century. We loved him. The theatre was packed, and Enrique sat on a shallow, overturned bucket as Guignol outwitted the evil proprietor of Club Sandwich to get the francs that he owed Mama Swing, who didn’t even have money for a hotel and was forced to sleep out in the cold.

We ended the outing with ice cream from René Nardonne next to a slate grey river. It was the last time we’d be able to eat at a restaurant, but we were told one month until freedom and culture and normal life. You know, to save Christmas.

November

I held out hope that my December holidays could be cashed in on a museum day and eating somewhere on my ever-longer list. I had to laugh: my Spanish cellphone company informed me I’d start paying roaming on November 3, so I only used WIFI while at home (and I was ALWAYS home). We stopped spending money on entertainment, instead using our allotted one hour out of the house, time-stamped attestation in hand, to see how much of our one kilometer perimeter we could trace.

Life became mundane – gads! boring! – while in France. But we were in FRANCE. Where only the self-proclaimed gastronomic capital could have outrageous prices on every piece of produce but cabbage and fish that tasted like freezer burn at a fine dining restaurant. It rained every day and eventually the neighbor’s geese stopped honking.

December

I called Menchu on Tuesday afternoon to see if she was free. The Confluence mall, with its cheap parking and endless dining options, was our halfway point, a merging of both our rivers and our families and our shared experience. “Jo, muero para tomar un café” Starbucks and a long stroll to the car became a simple taste of freedom and we joked about how Madrid was wide open to the French, but we couldn’t venture further than 15 kilometers from our homes.

The month went by quickly. Packing, purging, eating through whatever was in our freezer. We planned for a Christmas with Ángel, Menchu and their children but prepared for a feast at home. The pandemic brought out the resourcefulness in me: we made wreaths out of paper plates, a nativity from a 12-pack box of Kronenburg. My car battery died, and I could somehow find a place to get it replaced after buying Christmas presents at Carrefour. The days ticked down, and it made me sad to think of the experience we had lost by moving abroad during a pandemic. For my husband, it was six months of torture. For me, it was six months of reminding myself how exciting everyday life can be.

C’est fini

As we pulled away from Chemin du Chancilier shortly before the end of 2020, I bouncily told my eldest to wave goodbye to his school out the window. Au revoir, Stèphane! Au revoir, petite section! He asked for the tablet as I felt tears prick the corners of my eyes. Down we went on the A-6, crossing the Presqu’île on a needle-thin bridge before turning south on the A-7, the gastronomic motorway between Paris and Marseille. Out past the refineries, the shabby outskirts, snaking down the Rhône towards the Mediterranean.

I left Lyon with a heavy heart. Maybe it’s because Millán began walking here, and Enrique got his first stitches as I held his hand and looked away (and onto the Château d’Annecy, what!?!?!?). Maybe because it was my chance to live in a country that has forever captured my heart, even if the chance to really do it right was muffled by a global pandemic (can we say it again? Fuck COVID). Maybe because I need some challenge on a more regular basis.

When you meet people and know that your connection to them is fleeting, every minute seems important. François. Odiel. Julie. Menchu. Natalia. I have been overwhelmed with the generosity and warmth of the few people we have met and even wrote the mayor a thank you note to express my gratitude that he saved Millán that spot at the crèche.

Into 2021

What I may have liked best about those six months in France was how simple our days seemed. Even in the ho-hum of daily life, even when we were shuttered away, once more, in our homes, I couldn’t shake the tingly magical feeling. That we’d weathered a global pandemic, only to find ourselves more willing to try something new, to explore. And there were no extra distractions: no doctors appointments or social engagements, not always running off to see something and snap a few pictures. We had the space to grow together as a family over meals, trying to make sense of French pop songs and their odd music videos (Je te voie, Julièn Doré) or testing out all the snacks at the gas station as we visited little villages or explored further afield. I find myself craving the butter and cheese crackers that cost more than a 12-packs of cans of 1664 beer as I type.

There are little things about Lyon that have stayed with us: Millán’s favorite stuffed animal is called his beloved doudou, and Enrique’s birthday cake was a whimsical take on Guignol. We tend towards camembert when we can find it. I bought a six-pack of 1664 just because (I definitely didn’t get it for the taste) and work to French pop.

“You know we’ve been home for six months already.” The Novio is right, anything post-pandemic lockdown seems to have passed at warp speed since.

Home is where we are truly anchored. What we brought to France fit into my car, underneath kid feet or jammed into the crevices between seats. I brought a cheap bottle of Beaujolais jeune in Oignt on our third and final trip to that beautiful little village, and maybe we will drink it some day and reminisce about that time were were foules enough to move to a foreign country during a pandemic.

Yes, it was disappointing in many ways. I didn’t get the full experience I had been dreaming about since reading about the girl who lived in an old house in Paris, covered in vines. The French I learned was by way of a little green owl. The boys missed swim class and play dates and even catching a last guignol show.

Je ne sais pas, I still can’t put my finger on what France was. As the days fade into summer, as we plan for the long, hot months and the upcoming school year, I pine for it. Life seemed simple, simply because we had one another and a good rind of cheese and the balmy summer nights watching the sun set over the old farmhouse next door.

Am I vraiment folle for moving abroad during a pandemic? What other topics should I cover about Lyon or France?