Think of summer. Popsicles, parades, swimsuits (and if you’re me, likely a sunburn that sends you inside to pout about how you can never get a tan).

For me, summer is rarely synonymous with beaches and sunburns and barbecues, but rather pencils and books and scrambling for cash. Even though I am eligible for unemployment benefits when my contract finishes at the end of June each year, I nearly always work during the month of July to help pay for my tapas-and-beer binges and need to take advantage of my two months of freedom to travel.

Finding summer work in Spain can be both easy and frusterating. While many of my teacher friends choose to go home or just deal with the burn out in front of the air conditioner, I’ve compiled a list of jobs and websites that are available to North Americans (or otherwise) for the summer.

It’s important to know that tourism picks up during July and August, and most Spaniards have their holiday time during these months. This means unemployment takes a steep drop, and you can look for opportunities around Spain or even Europe.

Summer Camp Work

Like many other native English speakers, I have a ten-month contract as a teacher. The skills I use in the classroom transfer well to working at a summer camp, which can prove to be both intensive, but worthwhile and often lucrative.

What’s more, camps have gotten extremely popular for Spanish children whose families cannot afford to send their children abroad. Teachers can expect to earn from 500 – 1500€ for one month, depending on the job, hours, location and experience. If you’re at a residential camp, your housing and meals will also be paid for, allowing you to save up a fairly substantial amount if you’re smart.

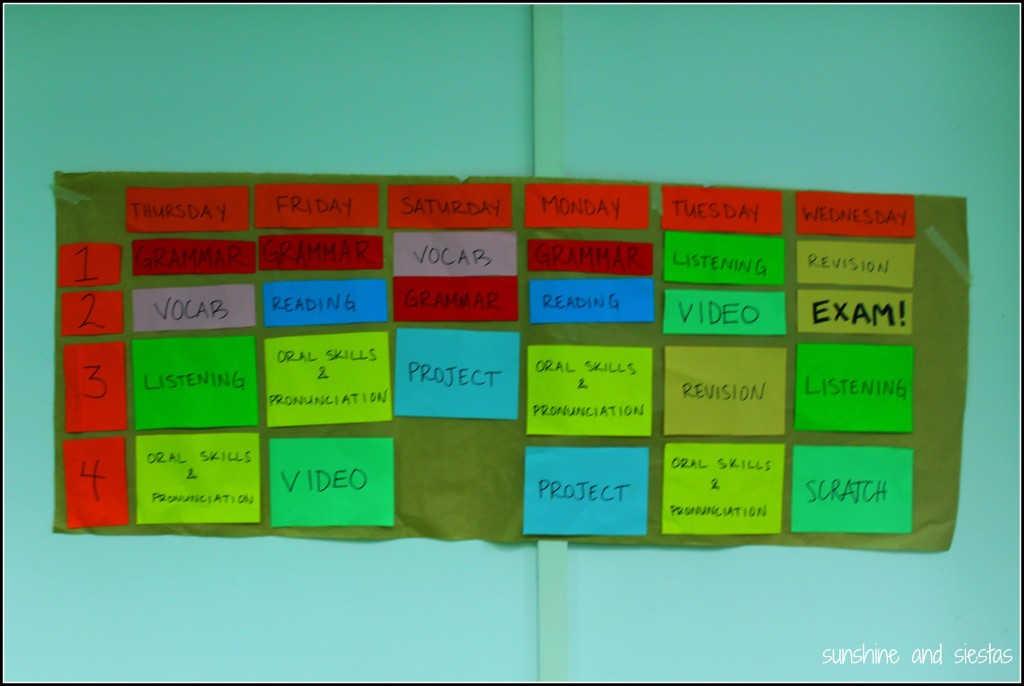

I personally have worked for Forenex Wonderful Summer Camps in La Coruña. Based out of Madrid, Forenex is one of the oldest and best-known combination sports/language camps for Spanish kids from 5 years and up. Successful candidates will work for 4-5 hours a day with small classes to improve oral fluency through fun, dynamic activities. A course curriculum is planned, but having control of your own classroom is a great way to learn and see if teaching is for you. There are camps all around Spain that provide housing and your meals, along with emergency insurance.

TECS is also a popular camp in Andalusia, based out of El Puerto de Santa María. Most of the camps are in rural settings around the Cádiz province and include extracurricular activities in English, so you can expect to be outside of a classroom setting a bit more. As a counselor, you’ll be both a teacher and monitor. You can apply for these positions, as well as coordinator gigs, on their Work With Us page.

Two newbies to the game, Village Camps is now hiring around the Chiclana area for native English speakers to be both teachers and monitors (and around Europe, too!), and Imagina English Camp offers a more rural experience in the mountains of Jaén (note that you must have work experience for this one).

If you’re based in Seville, SOL’s day camps look to hire around 15 teachers each summer, as does Proyecto Búho for several native speakers. It’s also worth checking out private schools in the area, as many have begun to offer activities and day camps.

Canterbury TEFL out of Madrid is another company that offers veterans of its programs positions around Spain in various summer camps.

Want to volunteer teach while in Spain? You can try the Diverbo Pueblo Inglés, where you will participate in various activities as a language instructor and be compensated with room and board. Should you have more experience, you can also try for a coordinator position. Check out their jobs page to see if Pueblo Inglés is for you, and be aware that they also seek out teachers for available positions for the school year.

Websites like Busco Campamentos, Dave’s ESL Cafe and TEFL.com are also places to look for academies that run summer programs or intensive classes in your preferred area of Spain.

Au Pair Work

Au Pair jobs give you free room and board and a bit of pocket cash in exchange for several hours of light housework, childcare and cooking. Not the most glamorous way to spend your summer, perhaps, but many of the families who take on au pairs will spend some time at the beach or a summer homes.

Word of mouth is perhaps the best way to go – ask any of the people you tutor, Spanish friends with young kids, at academies or private schools. Alternately, you could try websites and placement services. Before you go, it’s a must to read this great au pair FAQ about how to find a family and have a positive experience from my blog friend Alex Butts (and check out her blog – it’s SandS with just as much sass and great German beer).

Teaching Online

Very much the job du jour, you can use your morning hours to teach kids online from Spain through various companies. Many will offer lesson plans an competitive hourly salaries, whereas some can connect you to students in your time zone. Expect to make money in US dollars (so you’ll need a US bank account).

Tour Guide Work

Jobs for tour guides abound during the summer months. Try wineries, seasonal museums or outdoorsy attractions, or even see if you can get part-time work through contacts at your study abroad school. As most Spaniards take off for the summer months, you may be in luck (particularly if you speak multiple languages).

A great way to get your foot in the door is to contact the tour company beforehand to take a tour yourself, or to ask the owners how they got involved in the business. As my friend Natasha says, people love to talk about themselves, so take advantage!

Bar Work

If you’ve got work permission and are looking for short-term summer work, consider working in a bar or restaurant. Think Spain’s Jobs Page has many real-time listings for jobs in holiday areas, particularly on the coasts and at summer camps. It’s also helpful to ask around at hostels in the city you’d like to spend a few months in, or just up and move there and hope for the best.

Jobs can also include PR and promotion, such as handing out fliers to tourists at their resorts or other venues, slinging drinks or, if you’re lucky and connected, you might even score a gig as a VIP (free drinks counts as a job, right?).

Resort Work

The July and August influx is not just about Spaniards flocking to the coasts – many holiday-makers from the UK and Scandanavia, as well as the US, come to Spain. Along the coasts, you can find ample opportunities in resort towns to work. Forget about hotel reception – resorts in Spain have been reinventing themselves during the crisis, and jobs are available as child care workers, water sport instructors or even drivers and couriers. Tour companies also look to hire people to be on-the-ground logistics handlers, though this may require work permission.

Seasonworkers.com lists dozens of short-term work opportunities around Spain, particularly on the islands and along the coasts.

Hotels and hostels tend to fill up, so if you’re also looking for a place to call home during the summer, consider working at a hostel for a few hours in exchange for a place to sleep. Sites like Hostel Jobs (which also has forums on summer camps and resort jobs) and Hostel Travel Jobs have searchable databases with ever-changing postings.

Cat says: I was not paid in any way to promote any of the jobs or companies posted here. Considering I get many emails regarding summer work, this post is purely informational and based on research and my own experiences. It is not, however, an exhaustive list, nor can I give you more advice than directing you to websites and giving ideas.

If you’re curious about working in Spain, visas, social security of have general enquiries about living in Spain, be sure to contact me on my other site, COMO Consulting Spain.