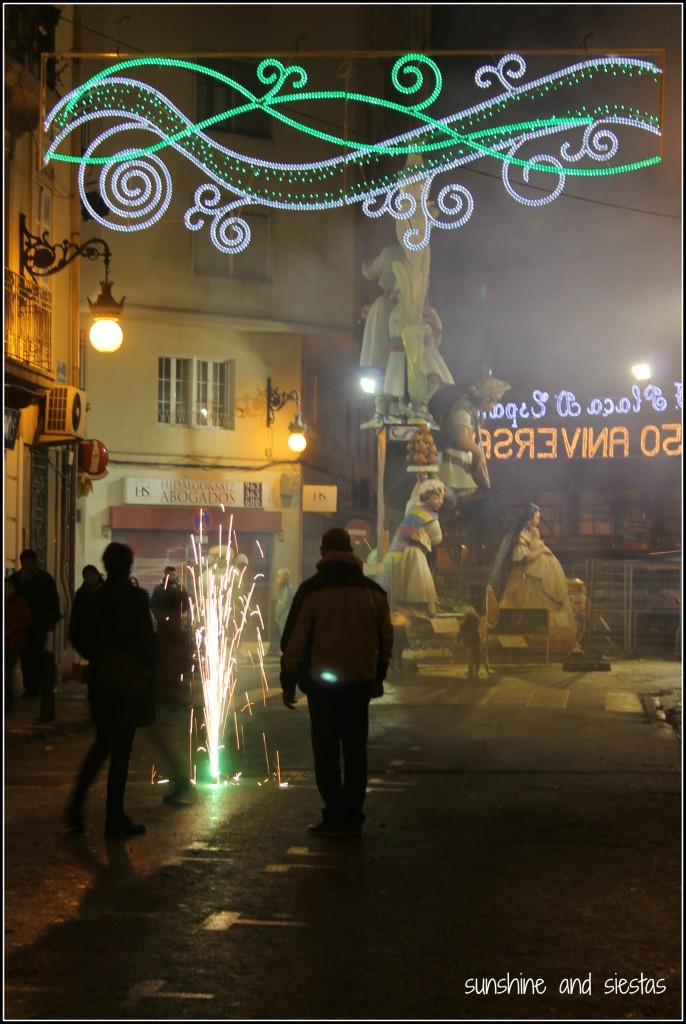

At nearly 6 am, small firecrackers still fizzled on the streets. I’d been awake for an entire day, driving from one end of Spain to the other before plugging my fingers in my ears every three minutes. This is Las Fallas, the Valencian festival celebrating Saint Joseph by burning a whole bunch of paper-mâiché effigies.

Fireworks and charangas? Well, color me hortera and show me the way!

I’ve used my Semana Santa holidays to explore the Balkans and India and had planned to walk part of the Camino up to Mérida in 2016. But when Valencia’s biggest festival falls during your vacation time and you have a friend offering up a couch, you curb your walking plans in favor of pyromania.

After a six hour trip from Seville, I parked my car at the end of the metro line in Torrent and hopped onto the train. Emily, a college friend, had recently moved to Valencia and into the trendy, central neighborhood of Ruzafa.

Almost as soon as I’d surfaced the street with a duffel bag slung over my shoulder and a pillow stuffed under my arm, I was met with smoke. Smoke from kids lighting firecrackers in the street at their feet, smoke from the stands frying up churros and buñuelos. The streets of Cádiz, Sueca and Cuba had become an all-out festival chocked with food stands peddling stuffed jacket potatoes and corn, people carrying cans of beer and ninots, two-story high effigies that would meet their fiery deaths during the Cremà.

It took me nearly 30 minutes to traverse the narrow streets that had been shut down, save foot traffic, to find my friend’s place via portable wifi in Spain. The ninots – the valencià word for puppet – towered overhead, depicting current events, celebrities and political figures, as well as nods to Valencian culture. Traditionally, each pocket of a neighborhood has a special sort of brotherhood, much like Seville’s religious hermandades, called a casal. Each casal pools together money, time and resources to conceive and construct a ninot and then display it on a street corner in the days leading up to March 19th, the feast of St. Joseph.

Valencia has 750 casales with 200,000 members – about one-quarter of the city’s population. That made for a lot of ninots to see (pick up a map of the most popular from the tourism office or look for city patrons on the main thoroughfares and in booths.

Emily’s flat on the eighth floor near the market was close enough to the action but far enough that I could relax for a short time. I’d arrived just after the Mascletà, a daily barrage of noise emanating from the city’s main square. Em and I hadn’t seen each other since we graduated, but we fell into a rhythm, gabbing our way out the door and into the street to gawk at the ninots, cans of beers in hand.

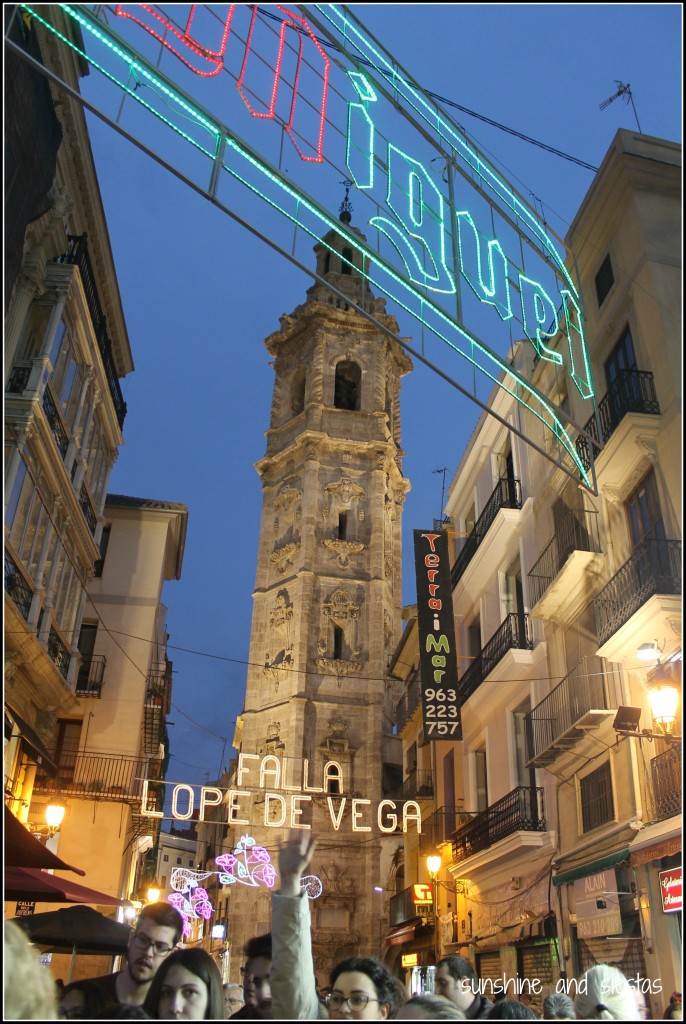

Ruzafa is not only the city’s hipster paradise, home to a dizzying amount of trendy eateries and bars, but a hotspot (pun intended) during Fallas. Every Haussmann-style street corner had a ninot stacked up to three stories and fanciful lights, arbor-style, surrounding them. Even in the middle of the day, young people stumbled around, throwing fizzlers into their wake. It was hazy, despite the overcast afternoon.

Crossing Gran Vía de Colón, we ran right into the L’Ofrena des Flors. One of the Novio’s coworker’s wife is a natural valenciana and gushed about this part of Falles in which falleros don traditional costumes and bring bundles of flowers to a towering Virgen de los Desamparados sitting in Plaza de la Virgen. Behind the barricades, I craned my neck and stood on my tiptoes to watch the casales pass by, arms full of daisies and sunflowers.

Women falleras take their garb seriously – like southern Spain’s traje de gitana, quality dresses are handmade, unique and costly. Come to think of it, dressing for Las Fallas was more like the Feria de Abril than I could have imagined. Consisting of a hooped skirt and bodice, they are typically made of pure silk and embroidered. Once you add the lace shawl and apron, shoes, jewelry and hair do, you’ve practically bought a wedding dress.

And it doesn’t end there – each casal elects a fallera mayor, who plays the part of hostess and attends to a court d’honor. This means food and fresh flowers for twelve people, much like entertaining in a caseta – and just about as costly.

Night was falling as L’Ofrena ended. Firecrackers sizzled under our feet as we looked for a tapas bar with room to squeeze into. It was drizzling and the center of town was packed with revelers. Dessert was a classic farton, a spongy cake made from sugar, milk, flour and eggs.

The night’s main attraction was surprisingly not pyrotechnics. Emily’s friends took us to an outlying neighborhood, Benimcalet, for a charanga. I confess: I have a soft spot for cheesy brass bands and Spanish wedding music. A small square was packed with people swaying back and forth to a rock band, and the old man bar anchoring the plaza served up cheap cubatas whose alcohol content was barely balanced out by soft drinks. By this point in time, I’d been up for 18 hours, and we danced and drank until the sun began to peek through the trees at 6am. I collapsed onto the couch, fully clothed.

A ripple of fireworks – the mascletà – rang through Ruzafa the next afternoon at 2pm. I was groggy, a product of both the deadly gin tonics from the night before and the crackle and pop from the rifles. I could already see smoke rising from the Plaza del Ayuntamiento.

I pulled on my boots and gulped down the coffee Em had made for me.Emily had already done her homework for the evening and had mapped out a route to see some of the city’s best ninots and lights displays before they’d meet their fiery end that evening. We spent the better part of the afternoon ducking out of the rain between visiting the city’s best ninots.

Popular lore says that the festival began as a way to burn off excess firewood on the spring equinox, eventually coinciding with the Feast of Saint Joseph, the carpenter. A typical piece of furniture burnt was the parot, a structure from which candles were hung. Over time, the primitive parots morphed into the effigies we see today, from rag dolls to elaborate, whimsical art pieces.

Like the chirigotas of the Cádiz Carnavales, the majority of the ninots poke fun at politics and current events. We saw quite a few Rita Barberás, the former mayor of Valencia who was indicted for fraud in 2016, as well as ponytailed Pablo Iglesias, Belén Esteban and the King.

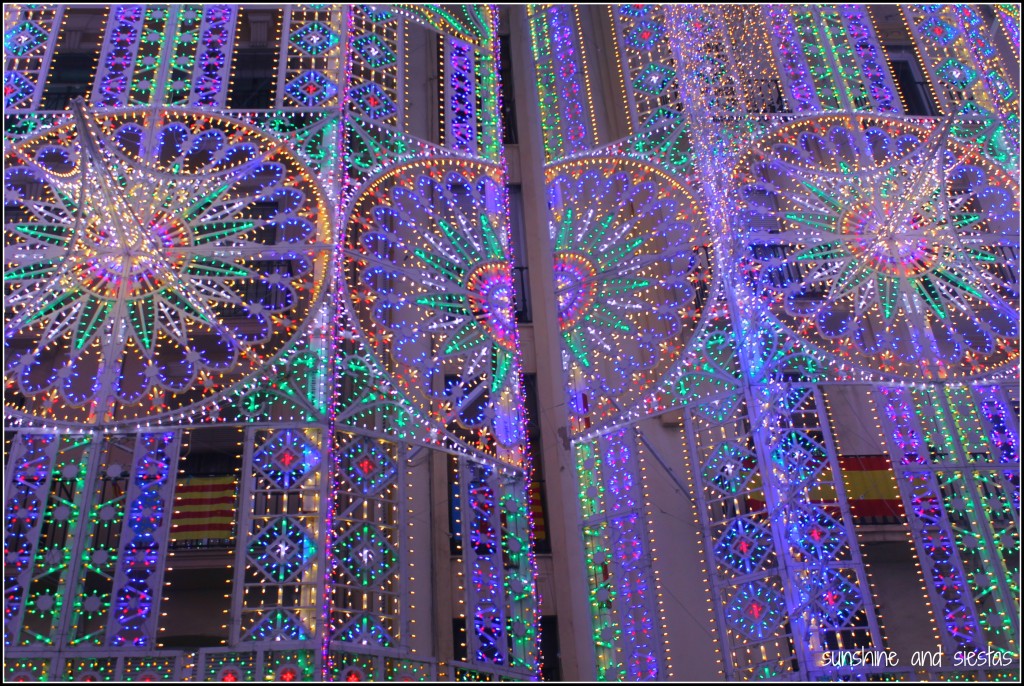

The rain meant we spent time drinking vermouths in Ruzafa’s trendy bars and watching the light shows on Calle Cuba. More than half a million colored bulbs glitter every hour after dusk, more than making up for the cancelled Cavalcada del Foc, a fireworks parade from Porta da Mar down Gran Via de Colón.

For hours, we powered walked, hand-in-hand, all over the center of the city, pushing past crowds and peeking into casales. The marquees were stocked end to end with tables and folded chairs, and scraps of food remained, untouched, in the centers. Falleras strolled in and out, often followed by a video crew.

As it neared 10pm, we were faced with a choice: nab a spot in the Plaza del Ayuntamiento to see the city’s falla be burnt at the very end of the night, or catch a falla infantil and one of the neighborhood fallas. We were at Convento de Jerusalén, just in front of the Estació de Nord.

This casal is part of the Secció Especial, amongst the most prestigious in the city (if you’re in Valencia before the Plantà on March 15th, you can visit all of the ninots and vote which two to save. They’re at the City of Arts and Sciences, and the expo is 3€ for adults and 1,50€ for children).

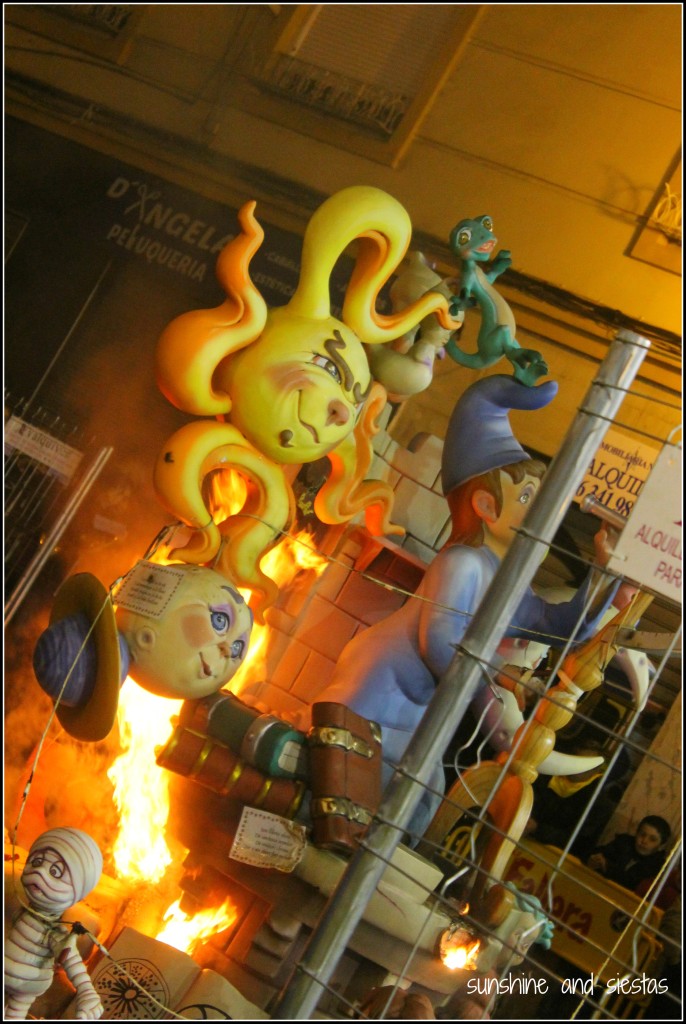

Just before 10pm, the casal’s fallera mayor and her pint-sized counterpart stood in front of the smaller, satire-free ninot. This close, you could see the fireworks-laden base that made up the whimsical, storybook creation. At 10 o’clock, the fallera infantil was introduced to the local media. She had a long string in her hand and tears in her eyes as a band made up of trumpets, drums and dolçaina – a reed instrument – struck up. She tugged on the rope, sending off a pinwheel of firecrackers that would eventually spark the effigy – something out of a bedtime story – in flames.

I fingered the earplugs in my jacket pocket, not sure if they’d do me much good against the deafening sound of firecrackers being lit across the city. My face burned from the intensity of the flames and the black smoke rising from every corner in Valencia, turning my camel-colored jacket a dingy grey. The small-scale puppet burned quickly, fizzling out with the help of a firehose in less than 10 minutes.

We rushed through the throngs of people back to Ruzafa. The streets had been difficult to traverse during the daytime, but the proximity to the main attraction – La Cremà – meant that we were pushing through crowds staking out a prime viewing spot. We’d wanted to see one of the Secció Especial ninots, but couldn’t push through all of the people quickly enough. Ducking onto a side street, we got a front row view to one of the neighborhood fallas, a wizard holding a key with a devil on the side. No one seemed to know the significance.

Emily snaked her way through the masses to a street vendor and got some snacks and a couple of cans of beer. Like Semana Santa, there was a degree of waiting around during Las Fallas.

Just before midnight, half a dozen firemen placed their helmets on their heads and stood poised to put out flames, lest they get out of control. The metal gates surrounding the sculpture were pushed back, leading festivalgoers to be crammed into doorways and even scrawl their way up light posts. I saw kids with firecrackers in their hands, ready to toss them at the open flames.

I glanced at my watch. At promptly midnight, the murmur reached a fever pitch and the firemen grabbed their hoses. I couldn’t see over the shoulders of the revelers in front of me, but heat rose from the bottom of my boots and up my legs. One of my greatest fears is dying in a fire (…and jellyfish), but stepping back from the flames was not an option. I had arms tangled in mine, elbows next to my ears and even a child underfoot!

As quickly as it had gone up in flames, the statue burnt to the ground, a mass of smoldering ashes in mere minutes.

We tried to get close to the Plaza del Ayuntamiento to catch the city’s gargantuan falla, which is burned after all others have met their fiery demise. From the front of the train station, we only caught a sliver of the multi-story statue of a faceless man’s blaze of glory.

I found it disappointing that every single ninot was set ablaze at exactly the same time. I likened it to having to choose a bunk on the first day of summer camp – you never really knew it if was the best one, if your friends were nearby, or if you’d be stuck next to the kid who talked in his sleep.

The whooping and hollering in the streets lasted until the following day’s mascletà. My head was swampy, a mixture of warm beers and smoke inhalation. I’d spend another day with Emily traipsing around the Jardines del Turia before stopping by the Quixotic windmills in Castilla-La Mancha and the UNESCO World Heritage cities of Úbeda and Baeza.

Like the Tomatina, Las Fallas was a festival I was glad to see once, but it didn’t spark (sorry, I am the worst) enough interest in me to go back another year. It felt like waiting in a long line only to be slightly disappointed when you had something shiny and new in your hand.

Perhaps we didn’t do it right. Perhaps the rain hampered the festivities. Perhaps I just didn’t feel the true emotion, my senses dulled after a long car ride and the inability to shake the damp. And as someone whose favorite holiday is the 4th of July, even Valencia’s fireworks and fanfare weren’t enough to move it to my top-of-mind when it came to Spanish festivals. It was a lot of fun, laced with beers and laughter and smoke.

If you go: Las Fallas is one of Spain’s coolest festivals and happens during the first three weeks of March, culminating with the Cremà on March 19th. Book ahead and consider staying in Ruzafa or L’Eixample, where you’ll be within walking distance of public transportation and all of the major casales. Also bring cash – lots of street vendors won’t accept cards. You can find an official 2017 schedule here as well as a map to all of the city’s ninots.

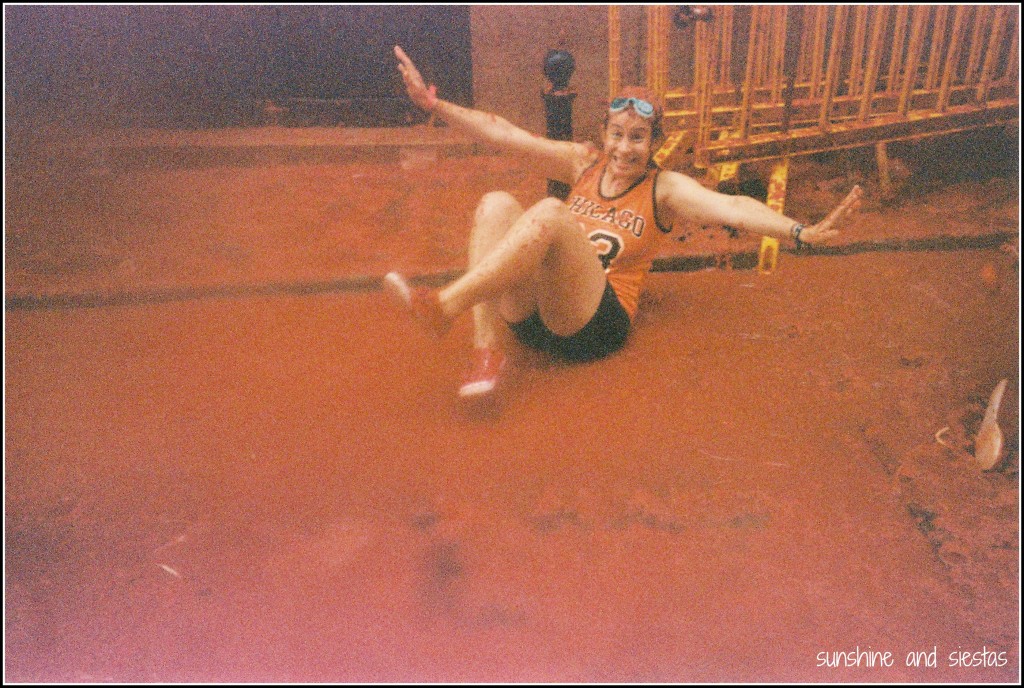

Valencia is a city I love more and more with each trip. Check out their crazy ice cream flavors, the UNESCO lauded Lonja de la Seda and the famous tomato slinging festival, La Tomatina.

Have you ever been to Las Fallas or Valencia?