“I’ll just stop talking before I ruin the Feria de Sevilla for you,” Dan remarked, noticing that I’d stuck my fingers in my ears. A history and archaeology professor at one of the city’s universities, he’d already struck down a number of things I’d known to be true about my adopted city.

In a city as mythical as Seville, I’ve become privy to tall tales and lore that have only grown to be larger-than-life legends in the Hispalense. But Dan’s early morning route with Context Travel astonished me with how many things I’d had wrong. Winding through the streets of Santa Cruz and the Arenal and speaking about the centuries that shaped modern Spain and the New World, I had to shut my mouth and just listen (always hard on a tour when you know so many of the city’s secrets!):

Gazpacho was invented by the Moors

Dishes with a legend are rife in Spain, and Seville’s claims to gazpacho are just as common. Gazpacho is a cold, tomato-based soup that pops up on menus as both a dish and a garnish. It’s also about the only Spanish dish I’ve mastered. While the word gazpacho is of Arabic origin, and they commonly ate a dish of bread, garlic and olive oil, the dish as we know it today is definitely is not of Moorish invention.

It a simple question of history: The Moors conquered the Iberian Penninsula over centuries, beginning in 711. The last were expelled in 1492 from Granada, the same year that the Catholic Kings sent a young dreamer, Christopher Columbus, to find a passage to India. Tomatoes come from the Americas, so the very earliest they would have appeared in Spain was the late 15th Century. While Moors lingered in Spain for centuries, the introduction of vinegar, tomatoes and cucumber would come much later.

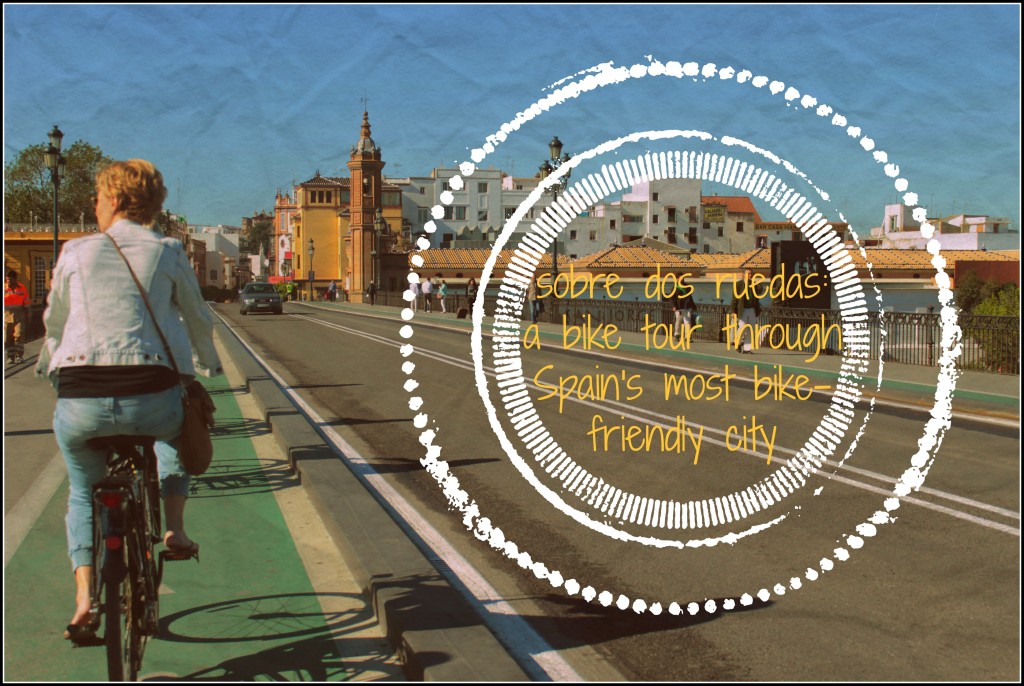

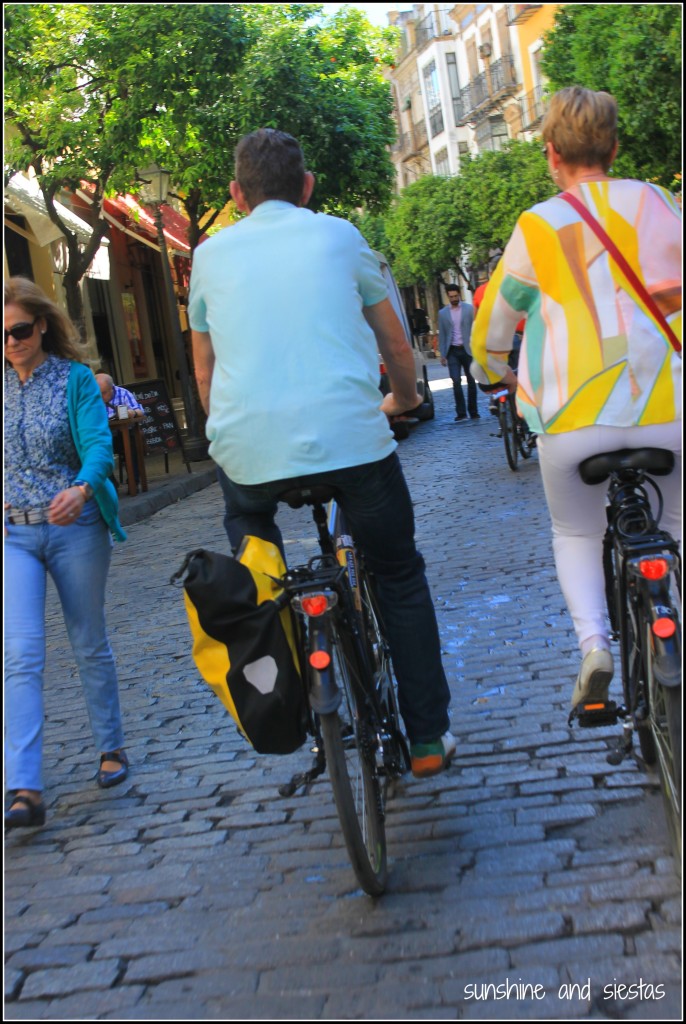

Seville is flat

Columbus may have been onto something else: for all of the boasting I do about how perfect Seville is for biking and walking, the city was built in Roman times around a series of hills. Little remains of the Roman past within the city limits, save a few columns on Calle Mármoles, the crumbling aqueduct that once carried water from Carmona, and the recovered mosaics and fish paste factory in the Antiquarium underneath Plaza de la Encarnación. If you want to see ruins, head to nearby Itálica or Carmona, or even two hours north to Mérida.

Roman Seville – then called Hispalis – had five major hills, with strategically built fortresses and temples built atop them. Laid out in a cross fashion, the major thoroughfares, called Cardus Maximus and Decumanus Maximus, and likened, to the main arteries of the human body, lead to a crossing near Plaza de la Alfalfa. This site was likely home to the forum, and Plaza del Salvador excavations have led archaeologists to believe the the curia and basilica once stood here. Indeed, the street leading from the east-west axis is the city’s one “hill,” dubbed Cuesta del Rosario, or Rosary Hill.

My glutes would be better off having some changes in elevation, but my knees are glad that silt from the Atlantic, which once lapped shores near to the Cathedral and old city walls, filled in the shallow valleys.

The true meaning of barrios

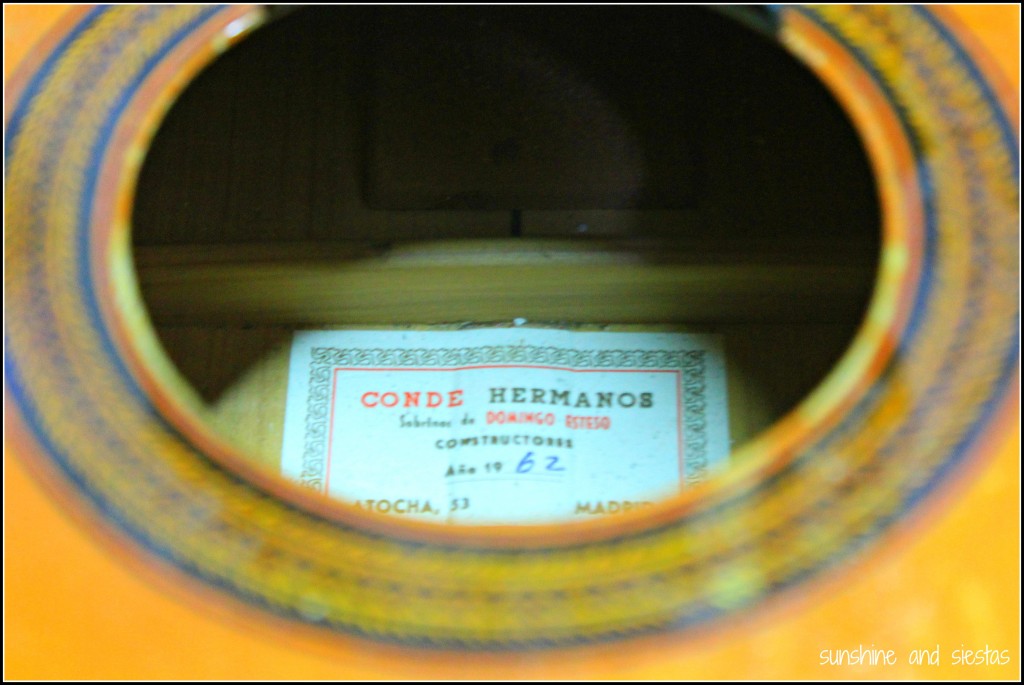

The streets of Seville are steeped in history, and many of their names give tourists a historical context. In my neighborhood, Calle Castilla stems out from the ruins of the Moorish castle, Calle Alfarería reveals where pottery and ceramic kilns once stood, and Rodrigo de Triana takes the name of the prodigal son who was reputedly the first to spot the New World from high in a crow’s nest.

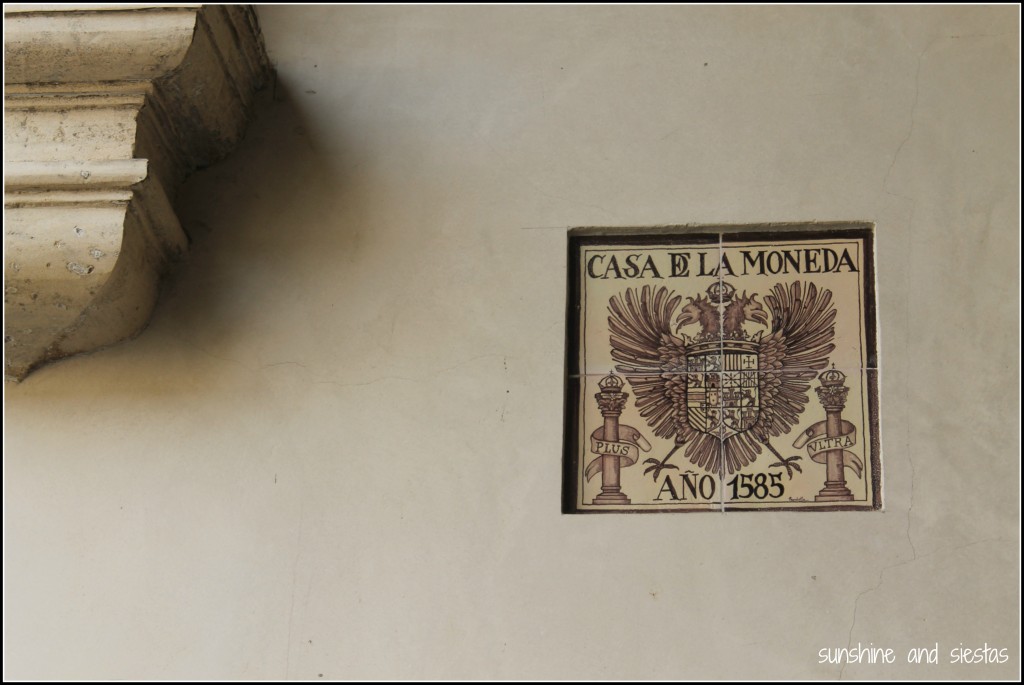

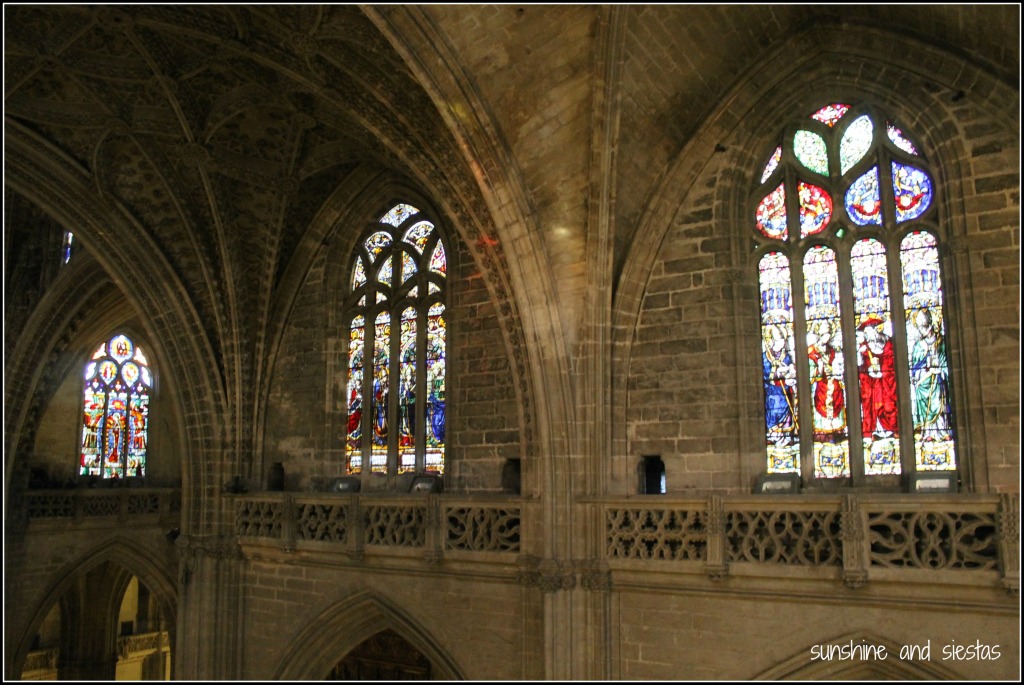

When Seville became a bustling commercial center after the Reconquist in the mid 13th Century, European merchants flocked from other ports of call to take part – population boomed, making Seville not only the most important city in Iberia, but also the largest in Europe.

Dan explained that competition was fierce amongst bands of merchants, and large manor homes were constructed around the cathedral to showcase not only the wares – olive oil was big business, even then – but also wealth. Just peak into any open doors in Santa Cruz, and you’ll see what I mean. Feudal relationships existed, and small gangs of street were established as territories, owned and operated by the merchant groups.

Because of this, streets bear names like Alemanes (German) or Francos (French). The wealthiest group? The Genovese, whose market wares were sold on Avenida de la Constitución – the most important street in the city center.

You may know another important genovés who passed through Seville during this time – he set off from Spain in 1492.

Triana was the historically poor neighborhood

Dan asked the other tour guests what they’d done since arriving in Seville the previous day. “Oh, we wandered over the bridge to the neighborhood on the other side of the river. Lovely place, very lively.”

“Well,” Dan replied, taking off his sunglass for effect, “Triana used to be one of the richest sectors of the city.”

I was baffled – I’d spun tales about how my barrio had once housed seafarers, flamenco dancers and gypsies, and thus made it more colorful and authentic, an oasis untouched by tourist traps and souvenir shops. In reality, the heart of Triana – from the river west to Pagés del Corro, and from Plaza de Cubs to just north of San Jacinto – was encapsulated in high stone walls and a number of manor houses during the Al-Andalus period in the 10th Century.

After the Christian Reconquist and subsequent destruction of the Castillo San Jorge, artisans, labor workers and sailors took up residence in Triana, perpetuating the stereotype that the neighborhood has been poor since its origins. Poor or not, it’s full of character and close to the city center, yet feels far away.

Orange trees are native to the city

I had learned the importance of citrus fruits in Seville’s culinary history during a Devour Seville food tour, and had wrongfully assumed that orange trees had been around since the time of the Moors. After all, they brought their language, their spices and their architectural heritage, so surely they’d thought to plant orange trees. Maybe they did – the Monasterio de la Cartuja is said to have edible oranges, and the cathedral’s Arabic courtyard is named for the naranjos that populate it – but it was renowned Sevillian architect Aníbal González who suggested planting orange trees along roads and in private gardens.

Hallmarks of the Neo-mudéjar visionary are littered around the city and other Andalusian cities, including his obra maestra, the half-moon Plaza de España. And Each year when the azahar blooms, I’ll be reminded that the Novio’s great grandparents wouldn’t have marked the start of springtime with their scent like I’ve come to do.

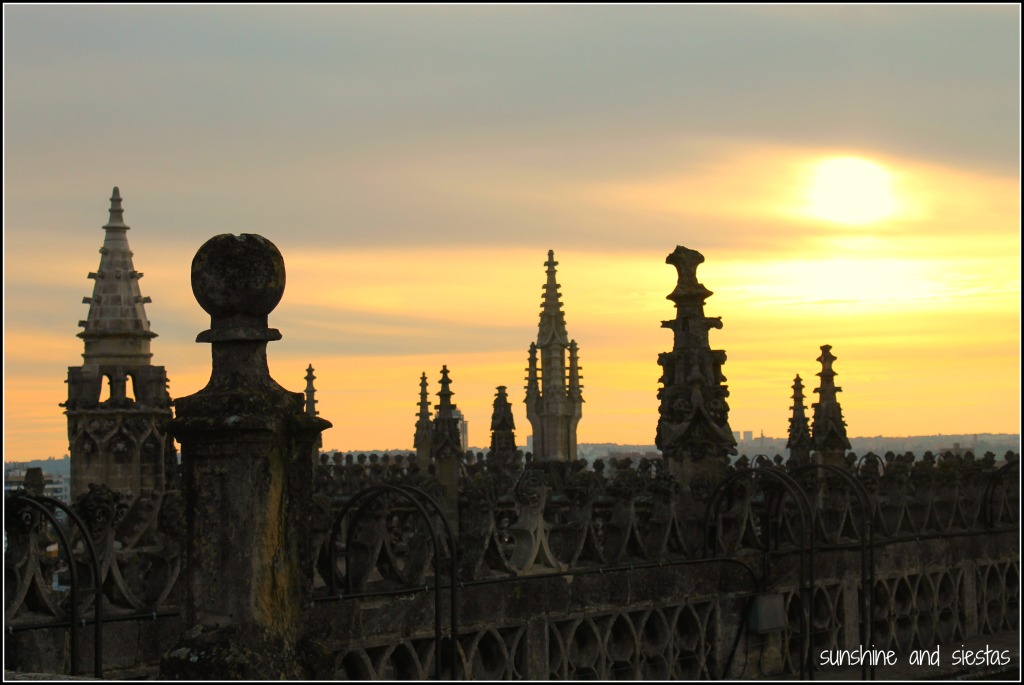

I’d spill more, but the tour will reveal dark moments during the Inquisition, hidden secrets from the bustling commercial period after the Reconquist, and where the New World archives actually are – it’s a tour made for history buffs and visitors who want a more inside scoop on a city’s political, geographical and historical origins. Admittedly, many of these facts can be found online, but the point is that locals perpetuate the incorrect myths as a way to keep the magical of the city intact. Sevillanos exaggerate, and these many of these tales are as tall as the Giralda itself.

Dan and I walked back over the Puente San Telmo towards Triana, and I offered to buy him a beer back in the barrio (even though he tells me I’m from the cutre part). One Seville myth that will never die: cerveza is cheap and aplenty in this city, and tastes best on a sunny day with friends.

Context Travel graciously invited me on the Seville Andalusian Metropolis tour free of charge; tickets are 80€ each ($91 USD at publishing), plus any entrance fees you may incur. Tourists are encouraged to tell the guide what things they’d like to see and explore to help give the tour shape – their tagline is #traveldeeper, after all! You can also look for them in Europe, North America, Asia and South America.

Are there any odd myths in the city where you live?